The Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay

/A piece of stern juts out of the water.

On the search for a hike “with water views,” my husband and I spotted Nanjemoy Wildlife Management Area on a map of southern Charles County, Maryland. We didn’t stop there (very small parking lot), but we made another great discovery—a park on Mallows Bay on the Potomac River where scores of submerged and semi-submerged ships form part of what is called a Ghost Fleet.

When we returned to kayak the area a few weeks later with Atlantic Kayak, we learned how and why they were purposefully sunk, most of them a century ago.

Fast, Cheap, Good—Pick One

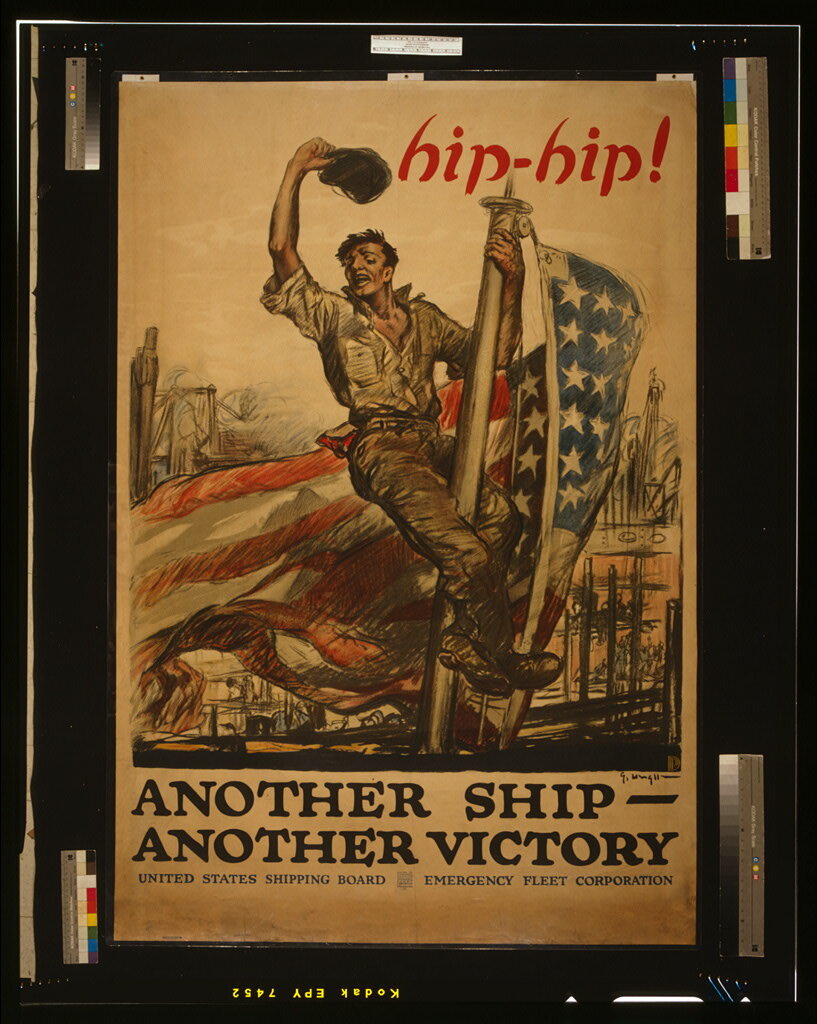

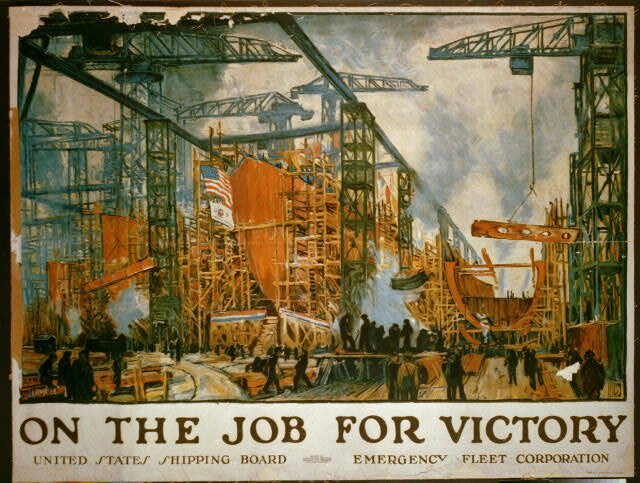

As the Great War (World War I) raged, America initially watched from across the Atlantic. Even without entering the war, however, we needed to build ships for commerce, as Germany sunk Allies’ ships by the hundreds. Once we had joined in, the need grew for warships, too. An entity called the Emergency Fleet Corporation began a massive sea-building project at 40 shipyards across the country. Propaganda posters in the Library of Congress photo collection shows rallying for the cause. But good intentions and patriotic spirit do not ensure success.

Only problem is that the ships were crap.

They were not well designed or constructed. Only a fraction were completed, and none made it to Europe. In any event, they were not needed when the war ended in 1918. No one wanted them and their chief value became the metal and other materials that could be salvaged. The wooden hulls remained an issue. In the late 1920s/early 1930s, they were brought into Mallows Bay, burned, and and sunk.

The hulls in the 1920s, which were burned and sunk shortly afterwards. From Library of Congress

The Festering of the Fleet

During the Depression, people nearby would dynamite pieces of the hulls to forage metal and other scrap materials to sell. During World War II, Bethlehem Steel had a contract to extract more materials, but didn’t get much out of the it. Other marine “stuff” was left there, including the most visible hulk as late as 1973—a car ferry supplanted by the Chesapeake Tunnel and Bridge.

Sanctuary

An aerial view shows the outline of the fleet. From Annapolis Museum Website

Potomac Electric Company (i.e., Pepco) tried to rid the area of the ships in the 1960s to build a power plant. Fortunately, it instead called attention to what became known as the Ghost Fleet. In 2019, the area was designated a National Marine Sanctuary.

Plants and wildlife have made use of the structures. People come to fish, boat, and hike.

It definitely has a far-from-the-city feel.