More on Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial

/This past week, I had a short article posted on Muster, the blog of the Journal of the Civil War Era. It was about a part of Alexandria’s Civil War history that has fascinated and inspired me—a successful protest and petition by hospitalized members of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT).

A mini-synopsis:

USCT who died in Alexandria were being buried in a civilian cemetery, rather than the military cemetery that was their due;

USCT patients organized a protest in late 1864, with a petition that quickly circulated and ultimately led to a change in this policy;

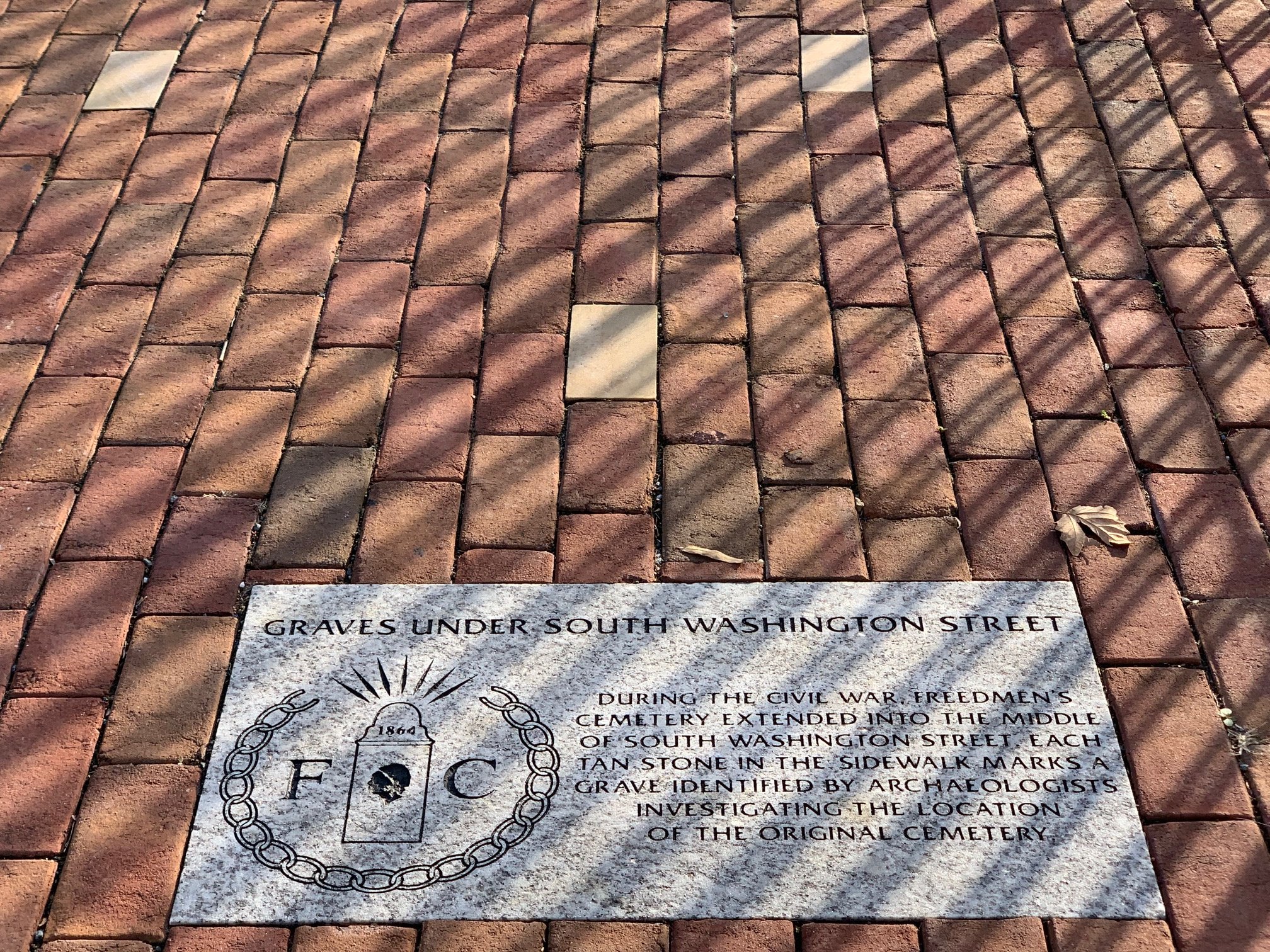

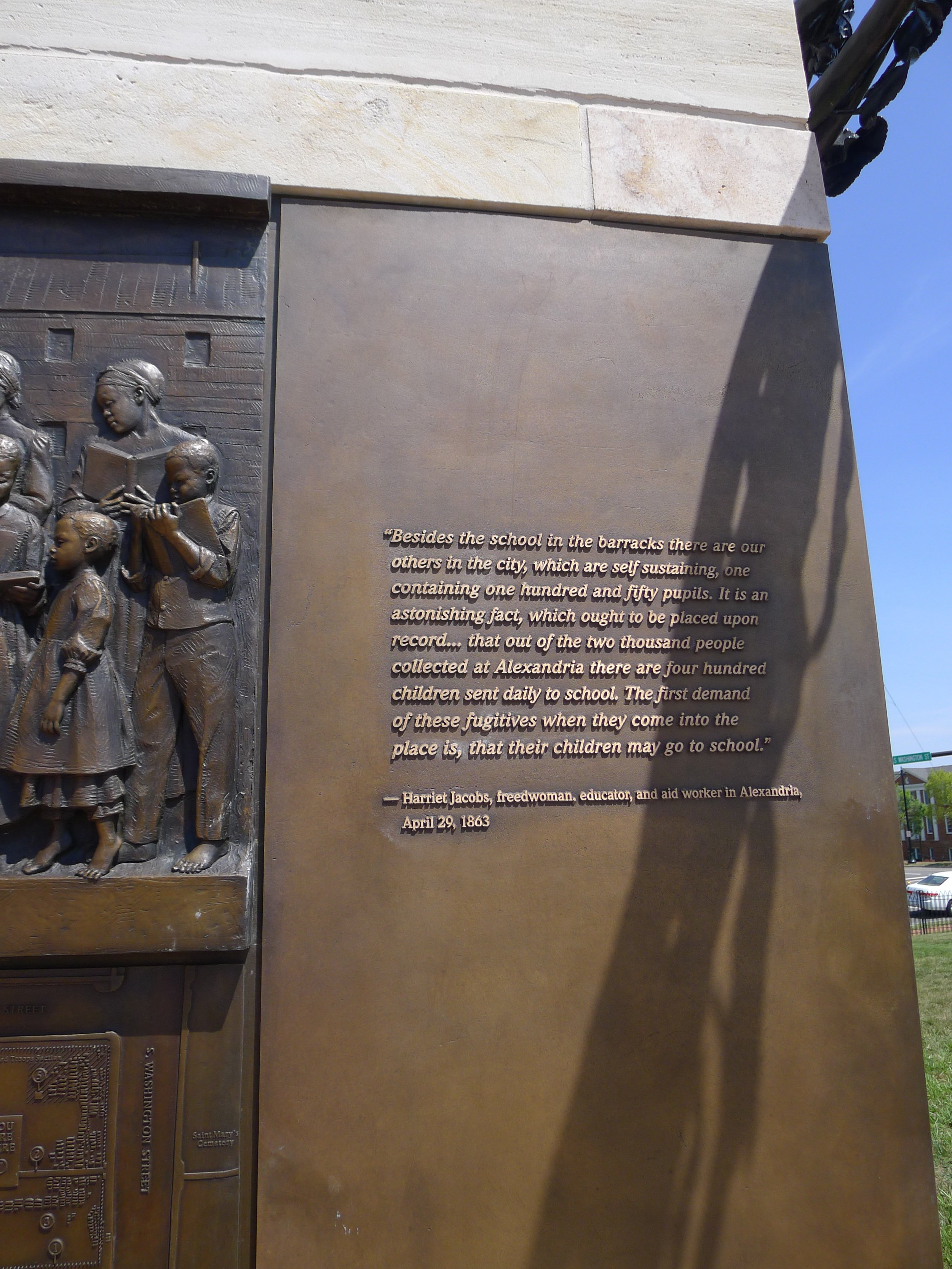

The civilian cemetery—re-dedicated as the Contraband and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial in 2015—tells their story and many others, and was recognized as a member of the African American Civil Rights Network in 2021.

You can read the full article here.

Given the word limit, I had to leave out a lot, including the full text of the petition, more photos, and questions that I still have. So here goes:

Petition Text

Louverture General Hospital,

Alexandria, Va. December 27, 1864

To Major Edwin Bentley,

Surgeon in Charge

Sir, we the undersigned Convalescents of Louverture Hospital & its Branches and soldiers of the U.S. army, learning that some dissatisfaction exists in relation to the burrial of colored soldiers, and feeling deeply interested in a matter of so great importance to us, who are a part and parcel with the white soldiers in this great struggle against rebellion, do hereby express our views, and ask for a consideration of the same.

We learn that the government has purchased ground to be used exclusively for Burrial of soldiers of the United States Army, and that the government has also purchased ground to be used for the burial of contrabands, or freedmen, so called, that the former is under the controll of Capt Lee, A.Q.M. U.S.A. The latter under the controll of Rev. A. Gladwin, Superintendent of Contrabands. We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army, we have cheerfully left the comforts of home, and entered into the field of conflict, fighting side by side with the white soldiers, to crush out this God insulting, Hell deserving rebellion.

As American citizens, we have a right to fight for the protection of her flag, that right is granted, and we are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest, and should shair the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers, who only differ from us in color,

To crush this rebellion, and establish civil, religious, & political freedom for our children, is the hight of our ambition. To this end we suffer, for this we fight, yea and mingle our blood with yours, to wash away a stain so black, and destroy a Plot so destructive to the interest and Properity of this nation, as soldiers in the U.S. Army. We ask that our bodies may find a resting place in the ground designated for the burial of the brave defenders, of our countries flag;

It has been said that the colored soldiers desire to be burried in the Contrabands Cemetary, we have never expressed such a desire, nor do we ask for any such distinction to be made, but in the more pertinant language of inspiration we would say, (Ruth 1:16-17) "Entreat me not to leave thee, for whither thou goest I will go and where thou fightest I will fight, and where thou diest I will die, and there will I be burried," and for this, your humble petitionars will ever pray, the unaminous voice of our Soldiers was given, and their names herin enrolled

(The names of the men, organized by ward, follow. Spelling as in the original)

Questions, Questions

History is all about learning something and wanted to know more. Such as—

Who composed the text and/or wrote it out? When I started learning about the action about 10 years ago, the most likely possibility to me was Rev. Leland Waring, who founded Shiloh Baptist Church next door. But a member of the Church showed me an old marriage certificate that he had signed, and the penmanship clearly did not match up. However, it is also possible that the petition was transcribed by someone else (a common task for Civil War clerks).

How did the organizers keep track of the names of all the patients? The petition lists 443 men—albeit with some mis-spellings and marks instead of full signatures. Still, think about the logistics of getting all names straight and explaining the purpose of the petition! Especially when (1) it all took place within days, and (2) the signers and petition circulators were wounded, ill, or both.

Is the placement of the first name on the petition— Sgt. Jessie Anderson, Company C, 23rd USCT Infantry Regiment—coincidental, or did he sign first as the organizer?

Why did Reverend Albert Gladwin, Alexandria’s Superintendent of Contrabands, bury the soldiers in the civilian cemetery? The Muster editor asked me this, and I suggested two possibilities in the article. I also read at some point that he may have received money for each burial so he had the incentive to bury as many people as he could/ I could not verify my source so did not include this possibility—but maybe?

Did the famous Quartermaster Montgomery Meigs really see the petition (as the story goes), and did his subordinate in Alexandria, J.G.C. Lee, really have no idea that his original order to bury the men in the Soldier’s Cemetery was being countermanded?

I invite your own questions, answers, and conjectures…

More Photos

These photos were taken at various times over the past few years. A visit yesterday unfortunately revealed that the metal signage is not doing well in the elements. (BTW, you may use these photos but please request permission before you do)

Some of My Related Blog Posts

About Dr. Edwin Bentley, the head of the hospital who was the initial recipient of the petition

About some of the brave men at L’Ouverture and and an amazing photograph

About the discovery and research related to the Memorial, based on a talk by former city archaeologist Fran Bromberg

About finding descendants, based on the work of genealogist Char McCargo Bah