Augusta Browne, 19th-century American female composer

/Most of us have not seen the words above—19th century + American + female + composer—together, but that was the story of Augusta Browne (circa 1820-1882), as described by biographer Bonny Miller. Her book, Augusta Browne: Composer and Woman of Letters in Nineteen-Century America, was published in 2020 by University of Rochester Press.

Augusta Browne was born in Ireland. When she was a child, her father moved the family to New Brunswick (Canada), then to Boston, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia to set up music academies. She taught and began to publish songs and piano pieces when she was about 16.

Bonny, herself an accomplished musician, discovered Browne’s articles and compositions in magazines of the time and first played one of Browne’s pieces at a recital in 1985. “Her story would not let me go,” Bonny told me. “The journey to uncover Browne's life led me on a merry chase for twenty-five years. I got to know her bit by bit, as fragments of evidence emerged over the years.”

Bonny also places Augusta Browne in the context of other women in the arts of the time. Conventions dictated by gender limited nineteenth-century women to certain creative artistic genres, whether in literature (poetry, short stories, essays, or novels rather than learned treatises), fine art (portraits and still life scenes rather than nudes, panoramic scenes, or monumental sculptures), or music (songs, hymns, dances, and piano solos rather than symphonies, operas, or sonatas). In addition to her creativity, “Browne’s modern aspects—entrepreneurship, networking, and use of social media of her era—captured my interest, especially for an era when we know few stories about businesswomen,” Bonny said.

Augusta Browne was a survivor. Here’s what else I learned about her in a recent email exchange with Bonny. You can learn more at her website. https://bonnymillermusic.com

You can also listen to two of Browne’s compositions in the links at the bottom of this page.

Q: I usually think of Europe as the place for music in the 1800s. What was the American musical scene like at this time?

A: Before recordings or radio, people had to make their own music. Nineteenth-century Americans participated in music in many venues—private, public, and semi-public. Concerts and public presentations typically mixed styles and genres of music. Programs with many different pieces and performers were the norm. Band music was more widespread than orchestral music, but venues for dancing and entertainment hired ensembles using whatever instrumentalists were available. Traditional songs were as common as tunes from operas of the era.

Huge numbers of songs were published as sheet music to appeal to many tastes, from comic numbers to sentimental laments. Love—whether for one’s sweetheart, baby, parent, God, or country—was a perennial subject for songwriting. The Victorian language of piety and sentimentality permeated parlor songs for the domestic market, including Browne’s lyrics. It may be hard for modern audiences to imagine how such stylized language and cloying sentiments could have appealed to a large population. But it was a time when people read sermons as frequently as novels, and flowery, elevated rhetoric was expected. On the other side of the coin, minstrel songs, with lyrics that presented appalling racial stereotypes, were extremely popular among white audiences.

Sheet music sold in large numbers. Personal collections were placed into bound collections, known as binders volumes. Hundreds of surviving binders volumes provide insight into music that family members played and sang at home.

Q: What were the prospects for a female composer in the 1800s?

A; It is important to note that there was no “foremost” American composer during the antebellum generations. Browne composed as well as most of her male contemporaries in the U.S. That said, women who performed and composed, like Augusta, often came from a family setting where they learned the skills they used professionally as adults. Training in music and art was limited both by access and content for antebellum American women. No academic situation (college, university, or music conservatory) existed in which she could have studied advanced counterpoint and orchestration.

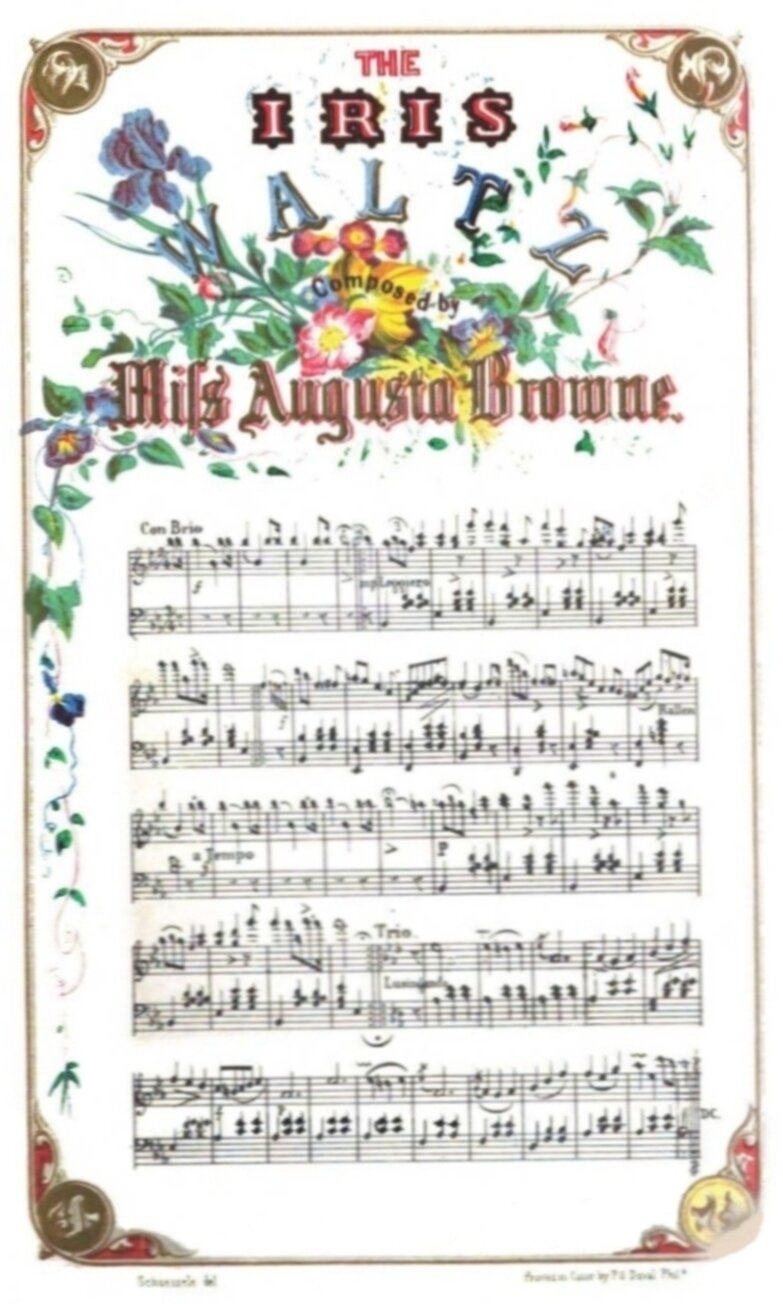

Browne’s first publications were songs and sets of variations for piano solo. Improvising or composing variations on short melodies was part of the music instruction that her father taught. She published at least 200 pieces in her lifetime. She was a skillful keyboardist and performed her own compositions in public concerts for charity causes as a young woman. Singing was a part of her family life, so songwriting was a natural outlet for her. She also loved the organ and held church positions beginning as a teenager.

Q: As we talked about, I am trying to learn more about pre-Civil War New York cultural and social circles related to writer Nathaniel Parker Willis & family. Augusta Browne also traveled through these circles. What was her life in New York like?

A: Unfortunately, no diaries or personal papers have surfaced for Augusta Browne. A few business letters exist, but we have to imagine her life without the benefit of diaries, family letters, or business records. She spent her days in a circuit of going to the homes of students to teach lessons in piano or voice. She was a faithful Protestant who attended church regularly, whether she was employed as an organist or not. She carried on vigorous correspondence with music publishers and periodical editors to place her music and prose.

Browne found sympathetic editors for her work in George Pope Morris and Richard Storrs Willis [NOTE: The long-time colleague and brother of Nathaniel Parker Willis, respectively]. Through her literary contacts, she engaged with other women writers of the era, such as Alice and Phoebe Cary, sisters from Ohio who held an ongoing salon in their home. Augusta’s youngest brother, Hamilton, was a gifted artist from an early age. His artist friends became her friends. She would have regularly attended art galleries and shows with her brother and his circle. [NOTE: No genuine photo of Browne is known to exist, so the cover of Bonny’s book features a wonderful hand-tinted etching of Lower Broadway at the time when Browne would have been traversing it.]

Perhaps through one of these events, Augusta Browne met and married a portrait painter, J. W. B. Garrett, in 1855. She was about 35 years old and at the height of her professional activities. She became a widow within three years, with no surviving children. The constraints of mourning, followed by the outbreak of the Civil War, cut deeply into her creative output for several years. Just as she was recovering professional momentum, the family decided to leave New York City in order to stay near another of her brothers, first in Baltimore, then in Washington, D.C.

Q: What else would you like 21st century readers to know about Augusta Browne?

A: She led a life constricted by gendered conventions that impacted what she could say, do, write, and compose. I admire the extent to which she got around such limitations within the era. Her entrepreneurship and self-agency suggest a modern individual, but her private life seems very old-fashioned. These contradictions define Augusta Browne to me.

A Sunday school teacher is not as appealing to many modern readers as a rebel or “bad girl” who defied social norms. But Browne could not afford to be a maverick if she wanted to work professionally as a church organist and as a music teacher of girls and young women. I’ve come to admire her strength and perseverance within the choices available to her. I doubt that I could have achieved as much as Augusta Browne in her milieu. She dared to aim high and wide using national magazines and newspapers. She persevered in self-constructing and negotiating a professional life even though men held every position of power. Browne ultimately wrote herself into history, and thus she controlled the narrative.

Q: How can we see and hear Augusta Browne’s music?

A: The ongoing digitization of nineteenth-century sources has made quite a few of Browne’s compositions available through such websites as HathiTrust, the Library of Congress, and the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection at Johns Hopkins University. Greater awareness of her life story and achievements will lead to more recorded performances of her music, but there are very few commercial recordings available at this time. I have played and recorded some numbers at home for my own use, and I have generated audio files of other pieces.

NOTE: Listen to Bonny as she performs two of Browne’s compositions—”Iris Waltz” (sheet music reprinted above) and “Courier Dove” (with Joy Calico, soprano).