A Conversation with Samira Meghdessian, Translator of Remembering Ramallah

/Wearing my billable hat, I usually do freelance work for organizations. During COVID, however, I took on a very different assignment. I worked with Samira Meghdessian, who had translated a book written by her uncle, Joseph Cadora, a former mayor of Ramallah, Palestine. He wrote a book in the 1950s about the history of his beloved city. Samira spent several years translating the book from Arabic into English, with some guidance from her cousin Fred (Joseph’s son), a professor of Semitic Languages. She extensively annotated the text to explain the many historic and cultural references embedded in the text.

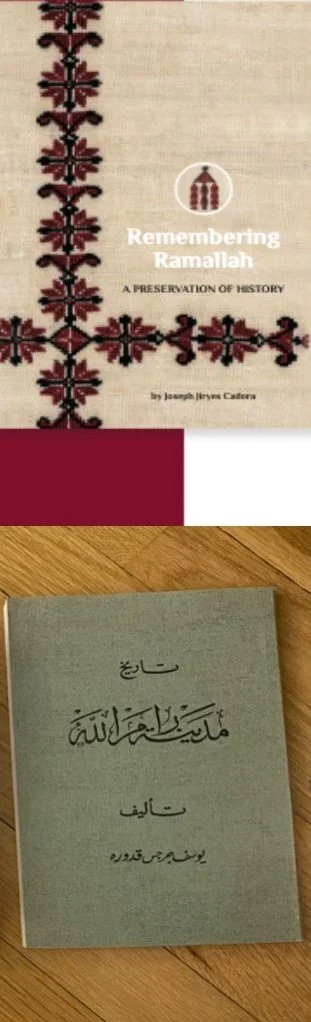

In early 2022, I turned over a Microsoft Word file to her and Fred. Since then, they revised the title (from History of the Town of Ramallah to Remembering Ramallah). More significantly, with the help of another family member, it became a beautiful finished publication. I recently talked with Samira about the challenge of translating a book that was more than 60 years old.

Q: Samira, for those who do not know, who was Joseph Cadora--professionally and his connection with you?

2023 English and 1958 Arabic versions of Joseph Cadora’s Book about Ramallah.

A: Joseph Cadora was born in 1893 in Ramallah. He came to the U.S. to train at the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy in Boston at the beginning of the 20th century. After finishing his studies, he returned to Ramallah and in 1924 and married my maternal aunt, Nameh Daoud Balat. He owned a pharmacy and later became Mayor of Ramallah from 1943-1952. He then returned to the U.S., where he died in 1958.

Q: With everything else he did, how did he come to write the book?

A: While he was Mayor, he had collected all the notes about Ramallah, its turbulent history, the customs of its inhabitants, its development, and his work as mayor, as well as the work of other mayors. The details in the book came from his notes, historical and archaeological documents, and interviews with town elders. When he arrived in New York, he and my aunt lived with family and there he began writing his memoirs, which became the book. It was printed in New York in 1954 by a now-defunct Arabic printing press known as Al Hoda.

Q: Why do you think he decided to write it?

A: He witnessed an important period of history that took Ramallah from the fall of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, the British Mandate, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the West Bank becoming part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. And being its Mayor, in a leadership position he had access to dignitaries, commissioners, and important personalities, and he wanted to document all that.

Q: Why did you decide to take on the massive job of translating it from Arabic into English?

A: In 2016, I toured Ramallah with a guide from the Tourism Office. He took me to the historical part of the town and quoted Joseph Cadora as he pointed out the old buildings where the original clans lived. He said that many second generation tourists do not speak Arabic, and he wished that the book were translated into English so he can show it to them. I came back to the US and discussed the possibility of translating it with his son, Frederic Cadora.

Q: As you really delved into the text to translate, did you come upon any surprises or new discoveries about Ramallah and about your uncle that you did not know before?

A: Yes, definitely! I learnt a lot about Ramallah, which is the hometown of my mother and her family as well. My mother used to relate stories about the clan she is descended from. I began to appreciate local customs, especially the old folksongs which I translated and which taught me about village customs and daily life. These traditions don’t exist anymore, and that is why it is crucial to document them for future generations.

Q: What were the biggest challenges in translating the text? How did you overcome them?

A: Fred advised me to use two very well-known Arabic-English dictionaries, one by Hans Wehr and the other is called is Lane’s Lexicon. This is my first attempt at translating Arabic to English, and it wasn’t an easy task, because every Arabic word must go back to its third-letter root in order to locate its meaning in the dictionary. Arabic is my mother tongue and I am probably one of the last ones in the family who can read classical Arabic and speak it fluently. I did it to prove to myself that I can master this effort. I am proud that I was able to complete it. I consulted often with Fred over Zoom, discussing words and their origins as well as the context they were used in. Fred and I were very cognizant of the sensitivity of the information, because he and I wanted to remain faithful to the original text that his father had written. We spent many times discussing what his father meant especially when we could not get to the source of the information. And we were careful not to outguess the author and to remain faithful to his intent. Many of the expressions and words are not in use today and it was hard to translate them.

The original book did not have any sources or footnotes. It was very challenging to locate them, list them in a bibliography, and footnote many of the names. I relied on other history books of the period and librarian friends in the Middle East.

Q: I edited your translation and gave you a Microsoft file. It became a beautiful book. How was it designed and published?

A: You, Paula, started that process with us, and the fact that you had no knowledge of the Arabic origin of the manuscript was, I am sure, daunting. I was very happy that you were able to get the meaning of it and you were very instrumental in getting it organized by creating chapters where they did not exist. Your work was a test for me to see whether the translation can stand alone, to see how it can be read without referring to the Arabic text.

After you sent us the file, we went through several versions we worked closely with Joseph Cadora’s granddaughter, Nadia, who took over the design and printing of the book. She hired a designer who did beautiful work. Nadia said since this was the work of her grandfather, she wanted to see it finished in a nice and elegant way. We contacted one or two publishers who publish similar books, but we were turned down, because they thought it would be difficult to market and it would have a limited readership. So we had it independently printed instead. I hope it will be picked up by a publisher, but this is not an easy task!

Q: It must be very satisfying to have the book completed. What are you doing to share it beyond your family?

A: We printed about 400 copies for the time being. I feel satisfied with how it developed and ended, and very appreciative of the valuable assistance I got from everyone who was exposed to it from the beginning. I feel I have accomplished something even if it may not be commercially viable. I feel confident that it will take its place among other history books on Ramallah, as I said in my Introduction, this is proof that the people about whom it is written still exist and do have a vibrant history that merits to be written about.

To order Remembering Ramallah, written Joseph Cadora, translated and introduced by Samira Meghdassian, and with a foreword by Frederic Cadora, go to https://tinyurl.com/Ramallah-History