Julia Wilbur: Teacher and Equal Pay Advocate

/The end of the school year and a recent book talk that I gave for members of Delta Kappa Gamma (an organization of women educators) led me to think about another part of Julia Wilbur's identity before her Civil War work--as a full-time teacher from 1844 to 1858. From the start, she recognized and spoke out against unequal pay for male and female teachers.

Starting Out in Rochester

Coincidentally or not, Julia Wilbur's first diary entry (or at least, the first that still exists) begins with her exam to become a teacher in the Rochester school system. Already we see that she was not exactly a shrinking violet:

May 1, 1844

The morning gloriously bright. The air soft & delicious, loaded with the fragrance of a thousand blooming orchards...but I could not half appreciate its beauties for owing to peculiar circumstances I passed them almost unheeded. My mind perplexed, dreading I know not what. I could not enjoy the morning for at 8 o’clock A.M., I was on my way to the [Reynolds] Arcade with the intention of presenting myself before the board of Education of the City of R. which board consists of some half-dozen members, three of whom were assembled in the Office of the Superintendent...[A]fter satisfying themselves that I had really seen the inside of various treatises on various subjects & having ascertained that I did know how many letters there are in the Alphabet, that I did not know that E has the sound of short I in yes; that I did know that St. Helena belongs to the English...I was dismissed with a certificate testifying to my ability for taking charge of the Sen. Female Department in the City of R. for one month...

But now having determined to enter the school (but for a trifling compensation, it being generally supposed that teachers can live on air, though glad would we be could we always have a sufficient quantity of that). I felt more at ease & thought I might as well resign myself to a dog’s life with a good grace & with every appearance of Contentment…..

Settling In

Julia's first week might sound familiar to many a teacher, with frustrations and glimmers of hope:

May 6: The day is past. I am not quite discouraged….But if there is anything lovely concealed, it is so deeply imbedded in the primitive rock, that it will require a long operation of the rough hewer to bring any thing symmetrical to light.

May 7: Today the prospect appears more encouraging.

May 8: There are some fine little girls among those wild pupils.

May 11: After long week, went home to Rush [about 15 miles south of Rochester, where her family lived].

May 12: Spent a short half day at home & then drove towards the scene of my labors to commence another week.

Over the next 14 years, Julia worked in many different schools, identified by number (e.g., School #4 or #11) at the time. She watched many teachers come and go. Teacher burn-out was alive and well. Various methods were touted as the Next Big Thing in education. She even had to prepare students for "high-stakes exams": back then, oral exams that required memorization over "critical thinking," administered in public by a visiting tester.

One of my future projects, with the assistance of the Local History staff at the Rochester Central Library, is to map where her schools were located and perhaps more about each community at the time.

Rosetta Douglass, Student

Another project is to corroborate a situation that Julia described in her diary. While it squares with her personal beliefs and her growing confidence as a teacher, it has not been found when looking through materials related to Frederick Douglass and his family.

Thus, here is the story, from Julia's perspective:

In 1849 she set up her own small "select" or private school, which was a marginal enterprise financially from the start. On June 17, she paid a social call on the Douglass household. (We could call Julia an acquaintance of Frederick Douglass; not a "friend" but she reports various visits and letters through the years.) A day or so after the visit, she reported:

Rec'd R. Douglass this morning as a scholar. Expecting several others would leave but they have not yet.

In other words, she tried to integrate her school with Rosetta, then about age 10 and the oldest of Frederick and Anna Douglass' children. And she thought she would succeed.

She did not. White parents took their children out of the already-floundering school and she had to close it. As mentioned, I have not read elsewhere about Rosetta Douglass as Julia Wilbur's student. However, her father did enroll Rosetta in a prestigious female seminary, perhaps after this incident, and was outraged to learn that she was isolated in a room by herself. He hired a tutor to come to his home after that.

Equal Pay

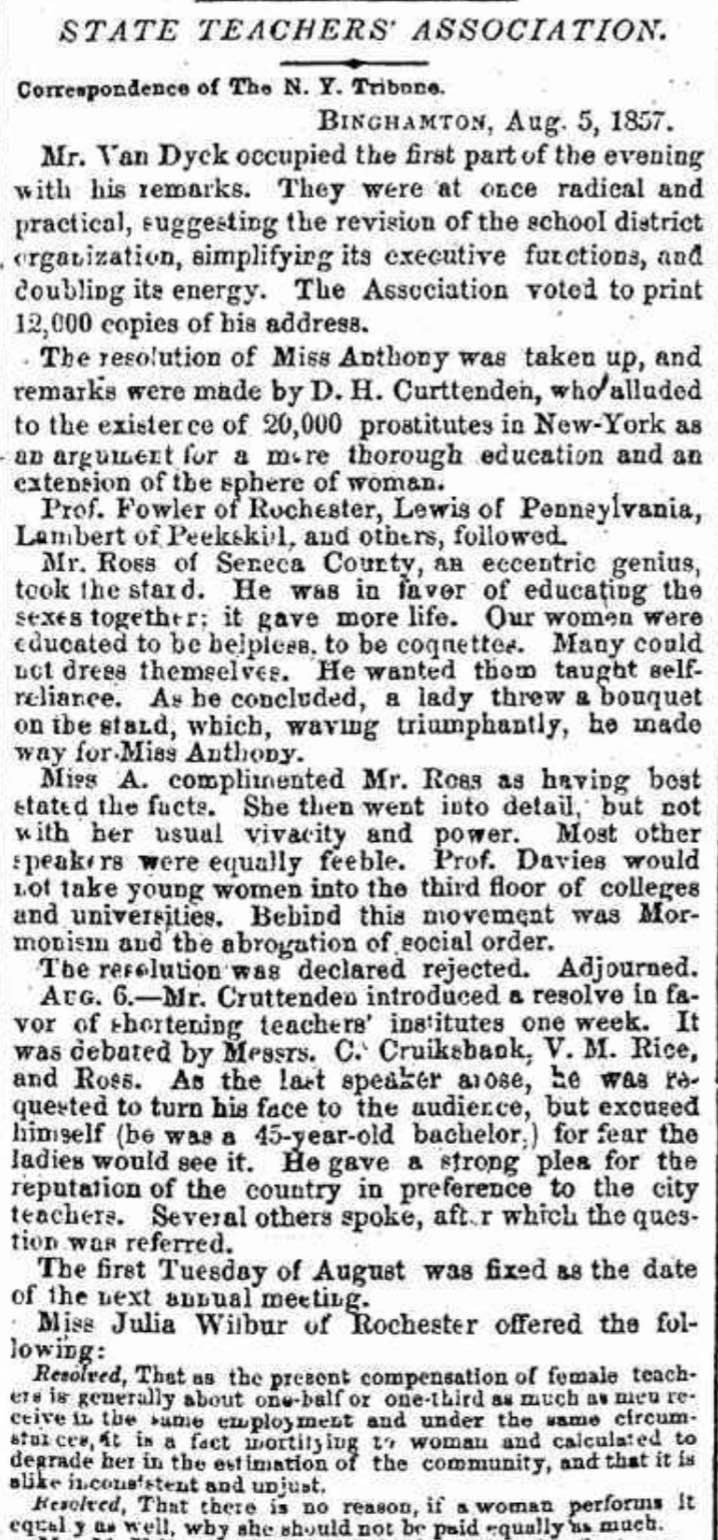

This article details the resolutions proposed by Julia Wilbur, supported by Susan B. Anthony.. It did not go in their favor.

Throughout her tenure as a teacher, Julia complained about the salary and the blatant male-female disparity. In 1857, she attended a meeting of the New York State Teachers Association and wrote:

The spirit moved me & this was my first speaking in public. A spicy time.

The "spiciness" occurred when she offered two resolutions:

Resolved that as the present compensation of female teachers is generally about one-half or one-third as much as men receive in the same employment and under the same circumstances, it is a fact mortifying to woman and calculated to degrade her in the estimation of the community, and thus is is alive inconsistent and unjust.

Resolved that there is no reason , if a woman performs it equally as well, why she should not be paid equally as much.

If you read the beginning of the article, there was also discussion on co-education, somehow prostitutes came into the discussion as "an argument for a more thorough education and an extension of the sphere of women." (No, I have no idea what Mr. D.H. Curttenden was getting at, either.)

As for Julia's resolution (which begins at the bottom of this clipping then goes one--contact me if you would like to see the whole article)--Since one of the arguments used was that women did not have to support families, Julia had at least one example of widows who took over their late husbands' positions, only to see a drop in wages. Susan B. Anthony, who was a frequent (and unwelcome) speaker at these meetings, backed her up. With some back and forth, the first resolution passed; the second did not.

The majority recognized the inequality but would not fix it.