Mason's Island: or A Bully Little Island in the Potomac*

/In June 1863, Julia Wilbur took the short ferry from Georgetown to Mason's Island for a picnic for the U.S. Colored Troops training there. But--

a picnic was to be held today. We supposed the soldiers were to be furnished with a dinner by the visitors. But a very few cd. get there from Alex. They cd. not get passes. I am told they went for passes, but were driven away from the office, & used roughly...

And about the place she visited:

Mason’s Island is near Aqueduct Bridge. This house built 1807 here was the summer residence of a brother of Sen. Mason. Slave quarters about it too. Headqrs of officers now. Col. Birney & others, good place for Camp. — There was music & dancing, but the soldiers were minus the Collation wh. was prepared for them in Alex. because so few people cd. be had to go there.

The USCT and collations, of whatever bounty, are long gone. Here is the entrance into Mason's Island, now Theodore Roosevelt Island, yesterday from the pedestrian bridge off the George Washington Parkway. Yesterday, my husband and I walked over along with joggers, small kids, and a group of Army guys visiting the oversized statue of TR.

Last week's Arlington Historical Society lecture about the island by Brad Krueger, a National Park Service cultural resource specialist, motivated me to visit again. The first time I visited was to write an article in 1979 for the Washington Post's Weekend section!

Below are highlights from Krueger's talk, with some additions from Julia Wilbur's diary and other sources as noted..

Location Basics

The island is about 90 acres and sits near the Fall Line, the natural landscape transition that generally divides the Eastern U.S. into the Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain. It divides the Potomac River into what is called the Georgetown Channel (DC/Maryland side) and Little River (Virginia side). It has wetlands, two high points, and a stream that separates the eastern tip from the rest.

Pilings from the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge, built in the 1960s, transgress a piece of the southern side. Most of the rest of the island is covered by forest, only about 80 or 90 years old, planted by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Archaeological excavations have revealed shards, animal bones, and the like that show Native American settlements from 1500 BCE, and especially from 750 BCE to 200 CE.

The Masons

The British claimed the area in the early 1600s, and the land changed hands a few times until 1717, when George Mason III purchased it. His son, George Mason IV, started a ferry service between Georgetown and Virginia in 1748, and ferries operated for more than 100 years. Mason was an author of the Virginia Constitution and Declaration of Rights, refused to sign the new U.S. Constitution on various philosophical grounds, and contributed to what became the Bill of Rights.

But this is a post about the island and not the Bill of Rights, so let's move on.

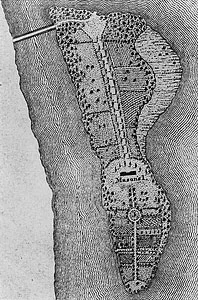

This map shows a causeway to the Virginia side, the location of the mansion, gardens, and roads.

His son, a Georgetown merchant named John, built a "pastoral retreat" on the island. It was grand. A tree-lined road led from the ferry slip to the classically built house. Its "famed gardens" included terracing and a variety of plants. An 1828 travel account by Anne Newport Royall described the house and its surroundings:

taking the whole together, it is the most enchanting sight that I ever beheld! A smooth, noble river in front...the dazzling flowers...the broad straight walks..the exact, level squares...the melody of the birds...

However,

Although this island, where we may say Nature keeps her holiday has so many allurements, yet it can be inhabited but a short part of the summer it being sickly...

Photo taken in the 1930s as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey. No vestiges remain; the CCC was very thorough. From Library of Congress.

The Masons lost the property through foreclosure. A story that they left because of the mosquitoes was perhaps concocted as a face-saving measure.

The island ran through several owners, none of whom lived on the island. In the 1850s, a man named William Bradley owned it and rented out the land.

Civil War

As Krueger explained, the Union Army first continued to grow food on the island. In 1863, however, they realized the advantages of using it for USCT regiments. About 700 men trained and lived there for just a few months (when Wilbur visited), away from the hostile reaction of many whites. When they deployed in early July 1863, it was used for temporary postings.

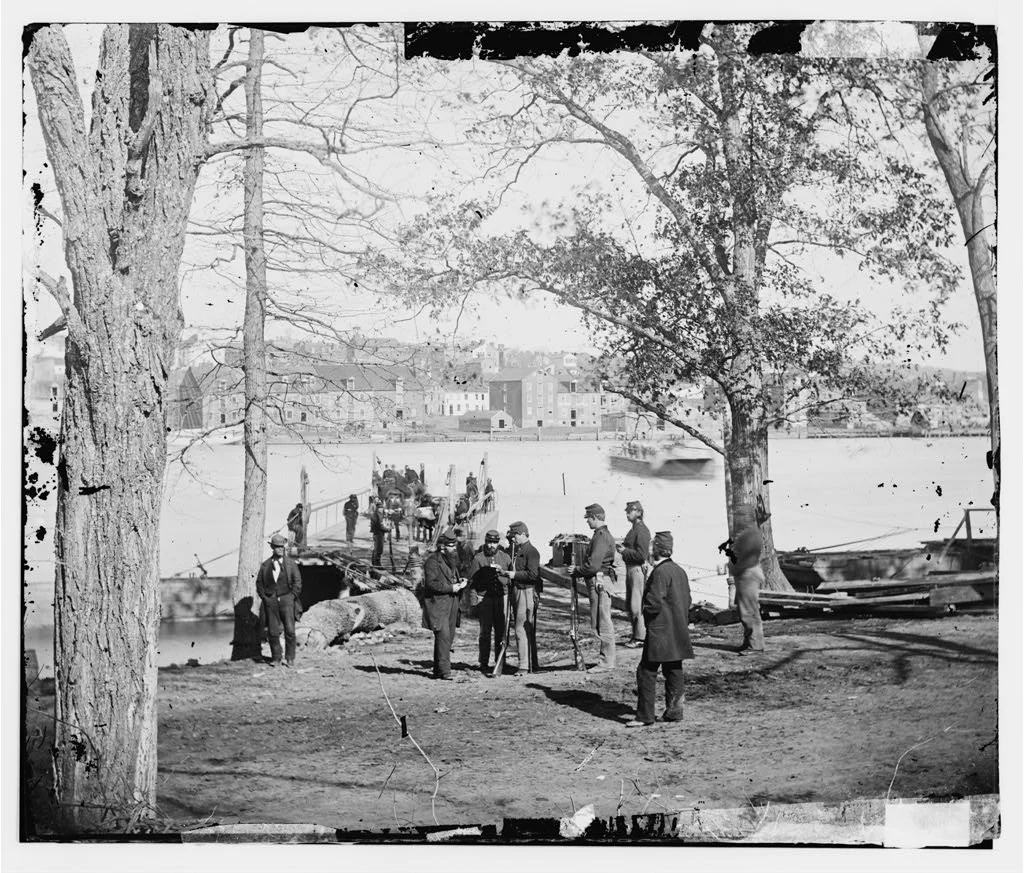

Inspecting a pass at the Mason's Island ferry landing. From Library of Congress.

In 1864, the barracks housed newly arriving freedpeople to northern Virginia--according to Wilbur, not necessarily with their active involvement. For example, she wrote on December 4, 1864, about a group of 58 people who managed to make their way to Alexandria from Petersburg:

There were several middle aged men, rather feeble looking. A great proportion were children, some were bare headed, some were barefoot, & they were all much chilled. We gave them some clothing, & food, & warmed them in the 2 kitchens. Then they were sent in 4 army wagons to Mason’s Island. They were good looking people & it seems a pity to have them sent away from Alex. If Govt. would give them shelter awhile & rations a few months, they would ask nothing further, but take care of themselves. Too bad. With a sensible Superintendent here, things wd. be different.

About a week later, on December 15, 1864:

Very cold. Nearly 100 persons were landed here this morning in a pitiable condition. No fire on the vessel, & no food for 24 hrs.—Some barefoot children, many were in rags. I gave about 30 pieces of clothing & Mrs. J. gave some. They were hurried off in 6 great wagons to Mason’s Isl. There were a great many small children. There should be a receiving room in the Barracks [in Alexandria] for such persons, where they could be warmed & fed, & stay long enough to find their friends, before they are sent away. Mr. Gladwin seems to have no feeling for them. The women & children came into the kitchen to warm. It was stowed full.

After the War to Now

William Bradley reclaimed his property, the Army sold off its structures, and the island ran through a few uses as a recreational facility, potential gas works, and other purposes. In 1831 an association purchased the island with the idea of turning it into a memorial for Theodore Roosevelt. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., designed a landscape--that's where the CCC tree-planting came in. The original plan was a kind of sweeping monument on the southern side of the island, but that is where the bridge was ultimately built after many years of opposition. Thus the current monument was built on the northern side. It features an oversize TR, and slabs with quotes on 4 topics near and dear to him: Nature, Youth, Manhood, and the State.

The CCC completely dismantled the Mason mansion, which was then seen as a crumbling eyesore. The only consolation was a thorough study of the site as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey.

The last remnants of the causeway were removed in 1979. Several attendees at Krueger's lecture had memories of it and the island as young people.

The island continues to evolve.

*In addition to Krueger's excellent presentation, I looked at a report prepared for the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS No. DC-12), available online through the Library of Congress.

AND, my June 1, 1979, article! Dan Griffin, the wonderfully clever, gentle copy editor (I can see him now, with, unfortunately, a cigarette usually nearby, he died 5 years later at age 47) gave it the headline I use above. I can picture him chuckling as he thought of it.