Story of a Photograph

/A few years ago, a man named Charles Joyce emailed me out of the blue. He had read the text of a small website I had put up on L'Ouverture Hospital, built by the Union Army in 1864 for black civilians and military in Alexandria. I wrote about the successful protest the soldiers had mounted in late 1864/early 1865 to demand that those among them who died would receive the honor of a military burial, along with their white counterparts.

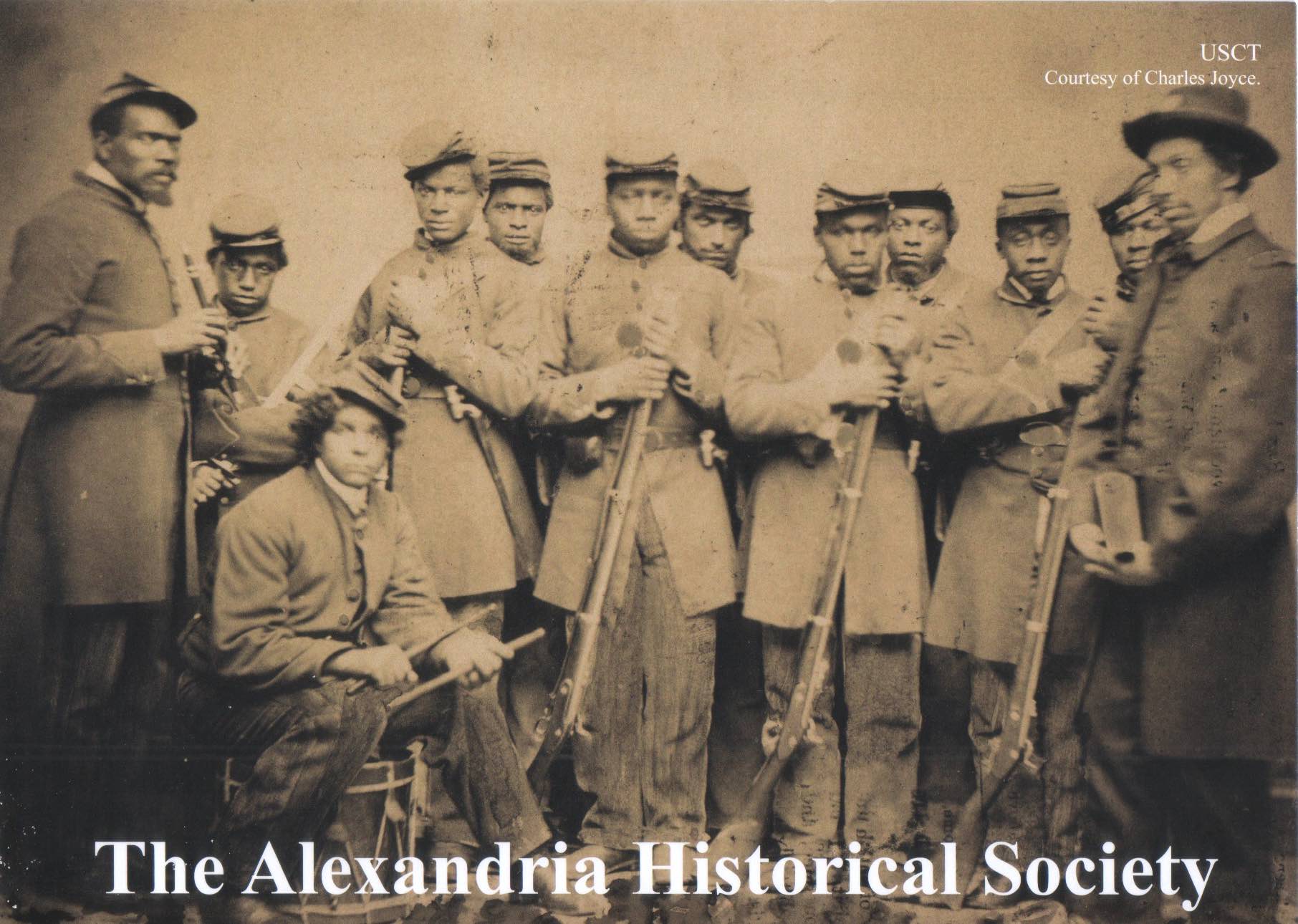

Charles had a photo of 11 U.S. Colored Troops and a man in civilian garb. Photos of USCT men are not common, in any event. But what made this photo truly special was that underneath, in pencil, someone had written each man's name. Instead of holding an image of brave but anonymous souls, Charles knew each person's identify. With a name, he could track down the story of each man. He did that and more.

I have been fortunate to hear him give two presentations on his research, including one this past week for the Alexandria Historical Society. He has also written an article, published in the Autumn 2016 issue magazine Military Images, and blog posts for the University of Kansas's Kenneth Spencer Research Library. His rendition is far more complete and compelling than this brief summary...

The Photograph

The original photo is about 9 by 7 inches, albumen (a method of the time), with some paint to spruce up the clothing, rug, and other elements (another common technique). Here is a scanned copy, as used by the Historical Society to announce the lecture.

From the collection of Charles Joyce

The Provenance

Charles found the photo in a box belonging to Franklin Snow. A young pacifist/abolitionist from Massachusetts, Snow did not serve in the military, but he did volunteer for the Christian Commission, which sent him to Alexandria in August-September 1864. (Julia Wilbur note: This was a time when Julia was sick in upstate New York. I wonder if their paths would have otherwise crossed?) His task was to visit hospital patients and generally make himself useful. His short stay left a lasting impression, based on his journal and letters. After divinity school, he moved to Kansas and became a professor and eventually chancellor at the fledgling University of Kansas.

As you will read below, the photo was taken after Snow left Alexandria. But Snow annotated it, and he kept it for the rest of his life.

The Men

Through records at the National Archives, Charles has found out something about each man--where he came from, his regiment, why he was at the hospital, and often more. Several had been enslaved before the war, including George Smith and Adam Bentley (second and third from the right). Others were freeborn, including William DeGraff (second from left), who became a corporal. Many ended up in hospital after the Battle of the Crater, an absolutely horrific conflict near Petersburg that resulted in large numbers of dead and wounded. Others were hospitalized for respiratory diseases, diarrhea and dysentery, common, often deadly afflictions of all Civil War soldiers.

The man on the far right, probably holding a Bible, is Chauncey Leonard, a prominent Washington minister who became one of the army's few black chaplains. Frank Snow worked under Rev. Leonard, who perhaps sent him the photograph later as they developed a warm relationship.

The Protest

As I have written in a few other posts, Alexandria's Freedmen and Contrabands cemetery was created in 1864 to accommodate the shockingly high number of deaths among the freedpeople coming into the city. It was an improvement from the overflowing paupers field.

But a problem arose: Although the deceased USCT should have been buried in the military cemetery, the superintendent of contrabands (and Julia Wilbur's nemesis) diverted coffins instead to the cemetery for black civilians. At the end of December 1864, a group of L'Ouverture patients had had enough. While it is unclear who was the specific organizer, someone (perhaps Leonard? or clearly someone else who was very eloquent) drafted and circulated a petition that quickly made its way through the hospital wards, signed by 449 men--including most of the men in this photo.

A small excerpt gives you an idea of what these men, many recently out of slavery, said:

...As American citizens, we have a right to fight for the protection of her flag, that right is granted, and we are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest, and should share the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers who only differ from us in color....

The petition quickly made its way up the chain of command to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs in Washington. The decision: Not only were the newly deceased to be buried in the soldier's cemetery, but the others were disinterred from the civilian cemetery and re-interred in the military cemetery, where they remain today. (You can read the entire petition, men who signed it, and transmittal letters in this article on the Freedmen's Cemetery site.)

According to Charles, the make-up of the group in the photograph reflects guidelines for a military funeral for a U.S. Army private: 8 rank and file men, a corporal, and solemn music (note the fife and the drum). Based on their hospital records, he dates the photo as taken within a few-month window, from December '64 to April '65. Perhaps, he conjectures, they gathered for the pose to mark the burial of the private whose death sparked the controversy. Perhaps it was for someone else.

The Aftermath

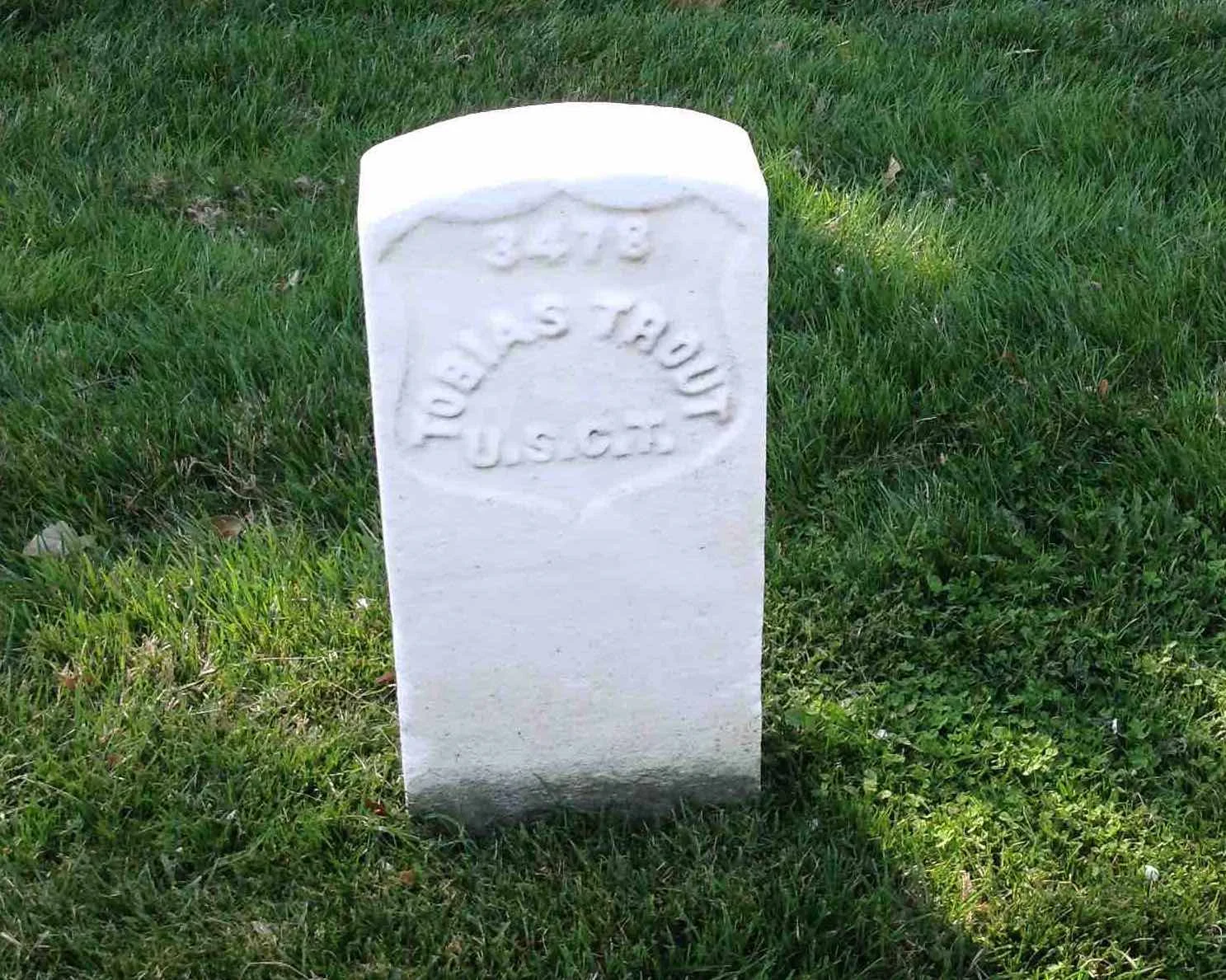

Charles tracked the what-happened-to-them-after-the-war stories of the men as best as he could, until the paper trails (usually in the form of pension records) grew cold. One of them--Tobias Trout, the tall man on the left with the fife--died on April 15, 1865 (as Charles noted, the same day as President Lincoln) and rests in the Alexandria Military Cemetery today.